Epidemiological overview and humanitarian context

Against the backdrop of war, the largest cholera epidemic in recent history continues to plague the Republic of Yemen. The epidemic started in September 2016, following a five-year lull in cholera outbreaks in the country [1]. As of January 2019, a total of 1,455,585 suspected cholera cases including 2,906 related deaths (case fatality rate of 0.19%) have been reported in the country since the beginning of the epidemic [2]. Children under five years old constitute 29% of reported cases [2].

Since 2016, three epidemic waves have been observed. The first and smallest wave occurred from September 2016 to April 2017 and peaked in mid-December 2016 [3]. The epidemic then drastically amplified from late-April to July 2017 in parallel with the rainy season [3]. At the peak of the second wave (late-June 2017), 50,832 weekly suspected cases were reported [3]. Cholera cases number gradually declined until the end of 2017 [3], followed by a third increase in case numbers in September 2018 [2].

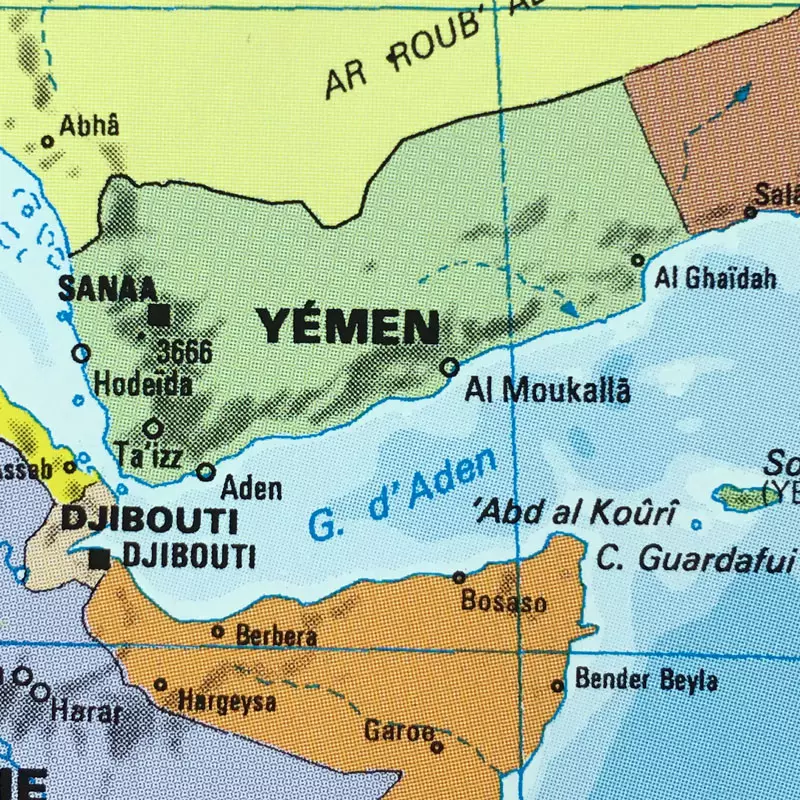

All governorates in Yemen have reported cholera cases with the exception of Socotra Governorate [3], which is an island archipelago located approximately 380 km south of the Arabian Peninsula. The five governorates with the highest cumulative attack rate (per 10,000 in habitants) since April 2017 are Amran (1,296.94), Al Mahwit (1,107.80), Sana’a (808.42), Dhamar (723.28) and Al Hudaydah (655.01) [2].

Ever since the war started in March of 2015 [4], bombing has destroyed water and sanitation infrastructure in some parts of the country [5], thus hampering cholera control and prevention and control. The main seaport to Yemen, Al-Hudeydah, was also bombed and later blocked, disrupting the supply of aid and other supplies into the country [6]. The United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs have estimated that more than half of the population in Yemen (17.8 million people) need assistance to access safe drinking water and sanitation [7]. Furthermore, approximately 19.7 million people need health assistance in Yemen, which is an increase of 3.1 million people in the last year [7]. The increased costs of food, water, fuel, medicines and other basic commodities has further hindered cholera control efforts [8,9].

Origin of the epidemic strains

Molecular analyses of clinical samples collected in 2016 and 2017 revealed that the strain responsible for the epidemic was Vibrio cholerae O1 El Tor serotype Ogawa. All isolates shared a similar phenotype of antibiotic resistance (decreased sensitivity to fluoroquinolones and resistance to nitrofurantoin, trimethoprim and nalidixic acid) [3]. Whole-genome sequence analysis revealed that all isolates from Yemen clustered together on the phylogenetic tree of the seventh pandemic, thus confirming that the first two epidemiological waves were produced by a single clone rather than arising from two separate introductions [10]. The isolates collected in Yemen grouped into a sub-lineage that originated from South Asia and then caused outbreaks in East Africa before appearing in Yemen [10]. The isolates from Yemen are most closely related to isolates collected from outbreaks in the East African countries of Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda from 2015 to 2016 [10]. Prior to the epidemic in Yemen, large cholera and acute watery diarrhea outbreaks occurred across the Horn of Africa, which serves as a major hub of migration into Yemen [10], thus indicating likely importation of the Vibrio cholerae strain from the Horn of Africa into Yemen.

Current situation

In recent weeks, Yemen has experienced another sharp increase in reported cases. Between January 1st and March 28 of 2019, nearly 148,000 suspected cases of cholera have been reported nationwide, including 291 related deaths [11]. Nearly a 150% increase in cholera cases was reported in March [12,13]. Children have accounted for more than a third of new cases [13]. Aid agencies continue to respond to the emergency, including UNICEF, WHO, International Rescue Committee, International Committee of the Red Cross and Médecins Sans Frontières [14]; however, they face many challenges including intensified fighting, access restrictions and bureaucratic hurdles to bring lifesaving supplies and personnel to Yemen [15].

---

References

1- World Health Organization (n.d.) ‘Cholera, number of reported cases (data by country) [Internet]’.

2- WHO (2019) ‘Cholera situation in Yemen: January 2019’. , (January). [online] Available from: https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/EMROPub_2019_EN_22332.pdf (Accessed 3 April 2019)

3- Camacho, Anton, Bouhenia, Malika, Alyusfi, Reema, Alkohlani, Abdulhakeem, et al. (2018) ‘Cholera epidemic in Yemen, 2016-18: an analysis of surveillance data’. The Lancet. Global health, 6(6), pp. e680–e690. [online] Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29731398

4- Human Rights Watch (2016) ‘Bombing Businesses: Saudi Coalition Airstrikes on Yemen’s Civilian Economic Structures July’. [online] Available from: https://www.hrw.org/report/2016/07/11/bombing-businesses/saudi-coalition-airstrikes-yemens-civilian-economic-structures (Accessed 3 April 2019)

5- WHO, JMP and UNICEF (2017) JMP Progress on Drinking Water, Sanitation and Hygiene: 2017 Update and SDG Baselines.,

6- Thomson Reuters Foundation (2015) ‘Saudi-led warplanes hit Yemeni port, aid group sounds alarm’. , pp. 1–3. [online] Available from: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-yemen-security/saudi-led-warplanes-hit-yemeni-port-aid-group-sounds-alarm-idUSKCN0QN0HX20150818 (Accessed 3 April 2019)

7- OCHA (2019) ‘Yemen: Crisis Overview’. [online] Available from: https://www.unocha.org/yemen/crisis-overview (Accessed 3 April 2019)

8- The World Bank (2016) ‘Pump price for diesel fuel (US$ per liter)’. [online] Available from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/EP.PMP.DESL.CD (Accessed 3 April 2019)

9- OXFAM International (2015) ‘Two-thirds of people in conflict-hit Yemen without clean water’. [online] Available from: https://www.oxfam.org/en/pressroom/pressreleases/2015-05-26/two-thirds-people-conflict-hit-yemen-without-clean-water (Accessed 3 April 2019)

10- Weill, François-xavier, Domman, Daryl, Njamkepo, Elisabeth, Almesbahi, Abdullrahman A, et al. (2018) ‘Genomic insights into the 2016-2017 cholera epidemic in Yemen’.

11- USAID (2019) Yemen - Complex Emergency (Factsheet #6), [online] Available from: https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/04.05.19- USG Yemen Complex Emergency Fact Sheet.pdf

12- International Crisis Group (2019) ‘Crisis Group Yemen Update #8’. , April 05, pp. 1–5. [online] Available from: https://reliefweb.int/report/yemen/crisis-group-yemen-update-8 (Accessed 6 April 2019)

13- Save the Children (2019) ‘1,000 children infected every day as Yemen cholera outbreak spikes’. [online] Available from: https://www.savethechildren.net/article/1000-children-infected-every-day-yemen-cholera-outbreak-spikes (Accessed 4 April 2019)

14- Federspiel, Frederik and Ali, Mohammad (2018) ‘The cholera outbreak in Yemen: lessons learned and way forward’. BMC Public Health, 18(1338), pp. 1–8.

15- UNICEF (2019) ‘Two years since world’s largest outbreak of Acute Watery Diarrhea and Cholera, Yemen witnessing another sharp increase in reported cases with number of deaths continuing to increase’. [online] Available from: https://www.unicef.org/press-releases/two-years-worlds-largest-outbreak-acute-watery-diarrhea-and-cholera-yemen-witnessing (Accessed 3 April 2019)